“Your whole existence becomes a series of interesting guesses.” – John Milton

First and foremost, this post is written from my perspective only. Every person involved in “Grace’s Journey”, including Grace herself, has their own perspective and experience, which are likely slightly different than my own.

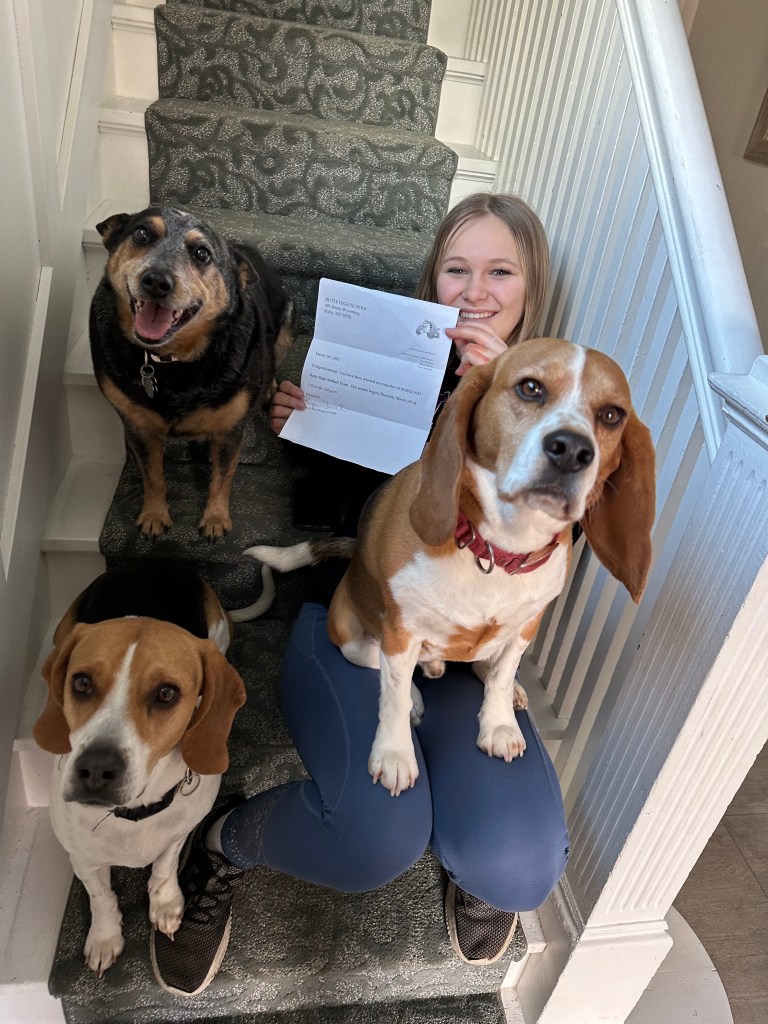

Grace’s symptoms first surfaced in the summer of 2023. She was playing on three different softball teams at the time, which meant a full-time schedule packed with practices, travel tournaments, and local games. She was practicing and traveling with her high school team, competing across the region with her traveling team, and squeezing in Little League games whenever her schedule allowed.

This matters because she was constantly swinging a bat and throwing a ball — both motions that involve heavy torso twisting. It made sense when she began complaining of pain on her right side, near her ribs, especially with movement. The pain would come and go, and although it wasn’t severe, it was enough to catch our attention. We assumed, along with her chiropractor, that she had simply stretched or irritated a rib from overuse. She was advised to take it easy and rest, but was reassured that the pain would subside and she could soon return to her normal activities.

A few weeks later, the pain escalated.

One night, Grace woke me up complaining of the same rib pain — but this time it was worse. The pain was no longer just on her side; it had started wrapping around to her back, deep inside, underneath her ribs. Tylenol didn’t help. When she rated her pain at a 5 or 6, we brought her to the emergency room.

After evaluating her, the ER doctors didn’t find anything alarming on the basic tests they ran. They concluded it was likely constipation — that a buildup of stool was putting pressure on her ribs when she moved — and sent her home with instructions to take Miralax. At the time, it seemed like the only explanation.

Grace took Miralax for months, often missing practices or having to sit out of games when she experienced what we started calling a “flare-up.” Over time, we began to suspect that her situation was more serious than what our local emergency room had suggested — but we had no clear answers to go on.

Determined to get more information, we brought Grace to her pediatrician, hoping for additional testing or a fresh perspective. Her pediatrician performed an abdominal ultrasound but ultimately reached the same conclusion: constipation.

Meanwhile, Grace’s episodes were becoming more frequent and more intense. She was now having flare-ups about every six weeks, and her pain levels were climbing — reaching 7s and 8s on the pain scale, often sending us back to the ER for pain management.

Frustrated by the lack of urgency and concern from our local hospital — after once being told, “there is nothing wrong with your daughter” — we decided to take Grace to the emergency room in Bozeman, Montana, a little over an hour away.

The doctors in Bozeman immediately took her case more seriously. They ran additional tests that had never been administered locally. Once her pain was stabilized — requiring strong opioids like OxyContin and morphine — they ordered an MRI, a CT scan, and a HIDA scan to check her gallbladder.

Still, nothing remarkable was found.

While they couldn’t provide a diagnosis, the Bozeman team recognized that something was clearly wrong. Trusting their instincts, they referred us to Primary Children’s Hospital in Salt Lake City. Without hesitation, we boarded a plane and headed straight there, desperate for real answers.

This was the moment everything shifted for me.

Up until then, I had been fueled by frustration — angry at the lack of answers, at the inadequate medical care in our small town, at the feeling that no one was really listening.

But as we boarded that plane to Salt Lake City, anger gave way to something much heavier: fear.

Real fear.

I was no longer just furious at what had been missed; I was terrified of what we might finally find.

I didn’t want answers anymore — not really.

I was desperate for a resolution to her pain, but terrified of the truth that might come with it.

We stayed in Salt Lake City for nearly a week, working to get Grace’s pain under control while multiple teams of doctors examined her and ran tests. The number of times we had to retell her story was astonishing — each time forcing me to relive the fear and uncertainty all over again.

On top of fearing the unknown, a new fear was creeping in: the cost.

At the time, I was working part-time selling real estate and finishing the final college credits for my addiction counselor license. I wasn’t working much, and the travel expenses and mounting medical bills sent a chill down my spine. Poverty had always haunted me — a fear rooted deep from the years I spent raising my three daughters in survival mode. Irrationally, that fear was resurfacing.

By the end of our stay, we had two different specialist teams who thought they had found the answer to Grace’s pain.

The first team — sports performance specialists — believed she was suffering from a rare condition called slipping rib syndrome, caused by excessive twisting and overuse of the muscles around her torso from softball. They recommended we see the leading researchers on the condition, based in Phoenix, Arizona.

The second team — gastroenterologists — had a much scarier theory.

After extensive testing, they wanted to diagnose her with chronic pancreatitis, a serious and life-altering disease. First, they needed some time, medications, and a diet change to test their theory.

Neither diagnosis explained everything.

The teams agreed Grace was likely suffering from both slipping rib syndrome and chronic pancreatitis. But no one could explain one symptom that had always stood out to me: the skin zaps and numbness she felt around her ribs.

Every doctor seemed to brush it off with a shrug — chalking it up to “the body is a crazy thing.”

By this point, we were over a year into Grace’s symptoms.

We scheduled another week-long trip — this time to Phoenix — to meet with the slipping rib specialists. Meanwhile, Grace was prescribed medications for chronic pancreatitis and put on a strict diet designed to minimize flare-ups. As a family, we felt a cautious sense of relief to finally have some answers.

But deep down, I knew something wasn’t right.

I had started reading everything I could about chronic pancreatitis, and nothing about Grace’s case added up. She didn’t meet the full diagnostic criteria. Some symptoms fit — but others didn’t.

Quietly, I began praying it was only slipping rib syndrome, that maybe after seeing the specialists in Phoenix and blocking the nerves around her ribs, the nightmare would end.

But if I was honest with myself, I knew it wouldn’t be that simple.

Somewhere inside, I was already convinced there was something bigger — and much scarier — waiting for us. I wasn’t ready for the truth, though.

We left Phoenix cautiously optimistic, hoping the worst was behind us.

The specialists had performed a nerve block they believed would stop Grace’s sharp rib pain and the strange skin zaps — symptoms they still couldn’t fully explain.

With the pancreatitis medication onboard and a strict low-fat diet in place, we expected no more emergency rooms. No more sleepless nights.

Instead, we began preparing ourselves for what life might look like living with a chronic pancreatitis diagnosis.

I refused to read the statistics about life expectancy for children diagnosed with the disease.

I couldn’t bear to.

And deep down, I still didn’t believe we had the right diagnosis.

In July of 2024, we took a family trip to New York to visit Brandon’s family and see where he grew up.

Along the way, we accidentally ended up in Atlantic City, New Jersey — a detour worthy of its own future blog post about rolling with the punches while traveling.

We were only supposed to stay one night before heading back to New York City to catch our flight home.

After a day at the beach and a night at dinner and the movies, I was jolted awake by Grace in the middle of the night — tears streaming down her cheeks, clutching her right side.

She told me we needed to go to the emergency room — immediately.

Without even asking, she blurted out her pain level: an 8 or 9. The pain scale had become second nature in our house by then.

Brandon, Abbie, Grace, and I rushed to the ER so fast that Abbie forgot to put on pants — literally.

In her half-asleep panic, she threw on a pair of shoes and walked out the door wearing nothing but a long T-shirt and Spider-Man underoos.

It wasn’t until hours later at the hospital that we realized she was still pantsless — a moment of comic relief we will lovingly tease her about forever.

Back to the emergency:

Brandon and Abbie dropped Grace and me at the hospital entrance and went to park.

As I walked through those front doors with Grace screaming in pain beside me, I felt something inside me break.

I wasn’t desperate for a diagnosis anymore — I was desperate for the right diagnosis.

I knew, without a doubt, that Grace didn’t have pancreatitis.

I knew slipping rib syndrome had been a swing and a miss.

Her screams in the ER lobby were so intense that staff mistook her for a woman in labor.

The ER physician later told us that, in 25 years of practice, he had never seen pain this severe — and had never struggled so much to get it under control.

Despite having taken her maximum prescribed dose of OxyContin at home before we arrived, Grace found no relief.

She was given Fentanyl, then morphine, before she finally reached a bearable state.

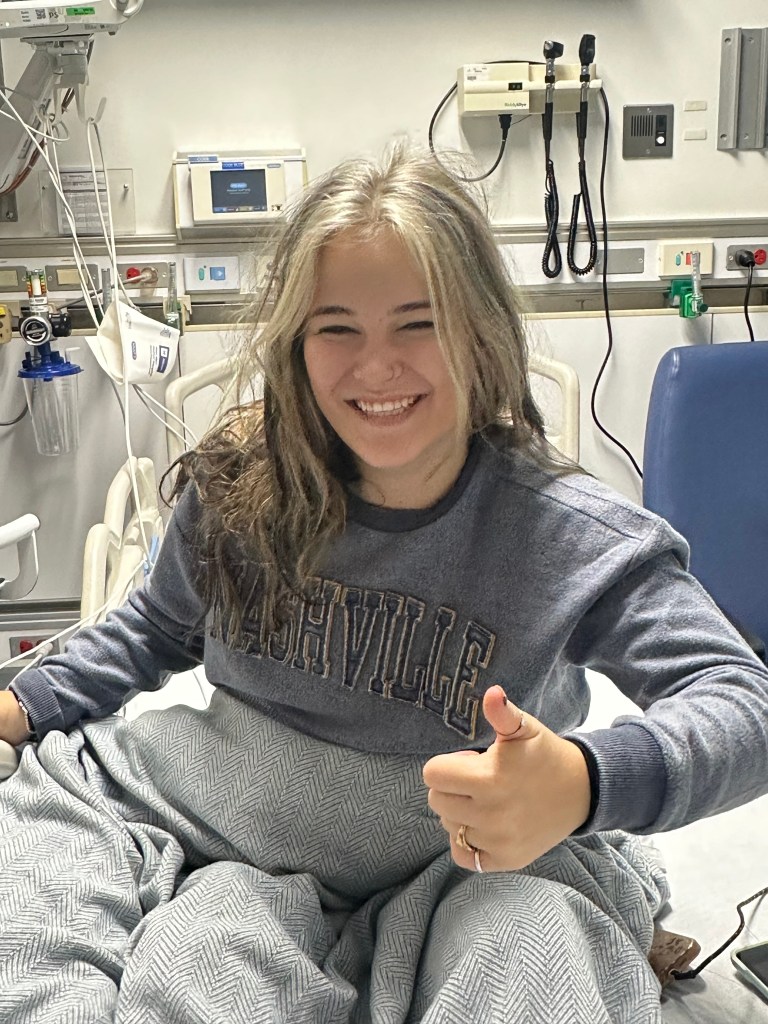

She was admitted overnight for observation while they tried to manage her pain.

We refused additional testing that night — we had already been through every test an ER could offer.

This wasn’t an emergency room problem. It was something bigger.

One critical piece of information did emerge from that visit: her bloodwork.

If Grace had been experiencing a pancreatic flare, her blood markers would have been elevated.

They weren’t.

Every number was perfectly normal.

With that final piece of proof, we left Atlantic City, made our way back to New York, and caught our flight home to Montana.

On the plane ride back, I scheduled another appointment with her gastroenterologist at Primary Children’s Hospital in Salt Lake City.

After forwarding the bloodwork results to the team and allowing them time to review, we returned to Salt Lake for another consultation.

During that meeting, the doctor admitted what I had long suspected:

Grace did not meet the diagnostic criteria for chronic pancreatitis.

She had followed the strict diet. She had taken all the prescribed medications.

But after six months, there was no improvement.

If anything, her flare-ups had grown more intense — and even between episodes, she lived with a baseline pain level of 3 to 4 every single day.

The gastroenterologist suggested referring Grace to neurology to explore the possibility that her pain was “in her head.”

Before doing that, he decided to run one final test — a liver function test — just to check every box.

He didn’t believe they would find anything.

Neither did we.

But that test held the answer we had been searching for all along.

During the imaging of Grace’s liver, doctors discovered something unexpected — a small spot at the edge of the scan, indicating a possible mass.

Additional specialists were called in to review the images.

They determined that Grace had a tumor growing in the nerve sheathing wrapped around her spine — hidden behind her liver and tucked under the ribs that had recently been nerve blocked.

How had this mass not been seen during the nerve block procedure?

No one had a clear answer.

But the doctors did have good news.

Based on the length of time Grace had been experiencing symptoms, and the “behavior” of the tumor on imaging, they were confident it was benign.

Even better, they believed it could be easily removed with surgery.

The relief I felt at that moment was beyond words.

After months of fear, doubt, and dead ends, we finally had answers — and more importantly, a solution.

No chronic illness.

No lifelong side effects.

No death sentence.

Just a surgery, and then, hopefully, Grace could return to her happy, active life.

I wanted to collapse into tears — tears of relief.

We scheduled her surgery for the following week.

But of course, nothing about this journey would be that simple.

When they performed further imaging to plan the operation, the surgical team realized that the tumor’s location would require a much more complex procedure:

They would have to de-stabilize her spinal column, remove the tumor, and then fuse her spine back together with rods and screws.

Still, it wasn’t cancer.

It wasn’t terminal.

It was hard — but it was manageable.

We moved forward with the surgery feeling hopeful.

On November 7, 2025, Grace underwent her tumor removal procedure.

The surgery was long, but it was declared a success.

That evening, we sat together in Grace’s third-floor recovery room, laughing, celebrating, and even giving the tumor a name:

Bruce — after Bruce Lee — because he had been kicking Grace’s butt for far too long.

For a few sweet hours, it felt like we had finally made it to the other side.

Until everything changed.

The next morning, the surgeon who had performed Grace’s operation came into the room.

There was something different about him — something heavy.

He asked Grace’s dad and me to step into the hallway.

We exchanged a glance, hearts pounding, and followed him into a nearby conference room.

A case manager was already seated inside.

The surgeon didn’t waste any time.

He looked at us with deep sadness and said:

“After removing the tumor and examining it under the microscope, our oncology team has confirmed… your daughter has cancer. I am so sorry.”

In that instant, the floor dropped out from under me.

And nothing would ever be the same again.

The moment those words hit my ears, my world fractured into a Before and an After.

And just like that, we were no longer fighting for answers — we were fighting for Grace’s life.

Leave a comment